Pacific Oyster

Scientific name: Crassostrea gigas (sometimes Magallana gigas)

Family: Ostreidae, the oysterfamily

Size: average 10-15 cm, but sometimes as big as 30 cm.

Distribution: worldwide

Status: not endangered

Visit our expo about the pacific oyster!

See also

External characteristics

The Pacific oyster is an elongated bivalve shellfish. Bivalve means that the oyster has two shell valves, just like a mussel. The shells are a colour mix of different shades of white and grey. In an adult oyster, the lower shell is curved and deeper than the upper shell. The shells are irregularly shaped with edges and ridges. Sometimes you can find barnacles on the shells of the Pacific oyster; these are small crustacean-like animals in a sturdy white house. Have you ever come across a Pacific oyster? Or maybe you've eaten one.

The Pacific oyster grows from April to October. From November to March, the oyster does not grow and may even emaciate [8]. This is due to the temperature of the water. They prefer a temperature between 11 and 34 degrees celsius. The rate at which they filter food from the water is also higher in the warmer months than in the winter months [8].

Did you know...

...An oyster can live up to 20 years old.

Oysters have growth lines, like trees do. These line are not easy to read, so we don't know how old an oyster actually is. [*]

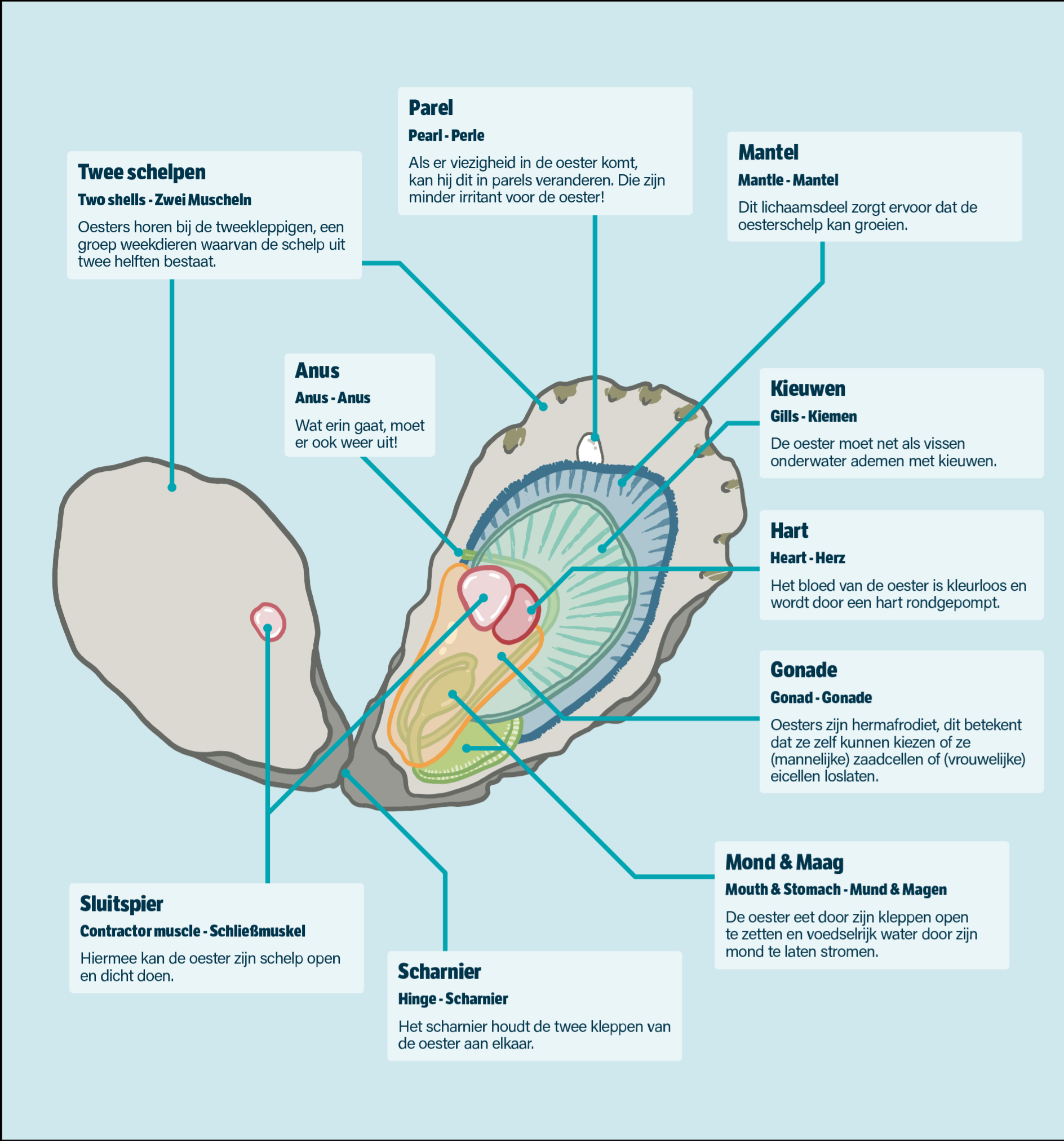

A Pacific oyster consists of the following parts [8]:

- Two shells

- Gills

- Mantle

- Mouth

- Mouthflaps

- Hinge

- Gonad

- Heart

- Contractor muscle

- Anus

Distribution and status

The Pacific oyster has its origins in Japan. But the animal is also native to Korea. The Pacific oyster thrives in cold waters and is widely used in aquaculture. Aquaculture is the farming of aquatic plants and animals. In the last century, the species was imported by humans into several countries, including the United Kingdom, the United States, Ireland, Australia and the Netherlands, to name a few.

Although it was intended to be used only in aquaculture to replace the native flat oyster, the species 'escaped'. Soon after, the animal began to establish itself rapidly in those countries. In addition, the species also accidentally ended up in countries like Norway, Denmark and New Zealand. This also happened in the Netherlands.

The Pacific oyster can quickly take over new areas with relatively little effort. They grow quickly compared to other oyster species, and are often better able to withstand pollution and disease. Because of their ability to establish quickly and compete with native species, the Pacific oyster is considered an invasive species (and sometimes even a pest).

Status: not endangered

There are concerns that Pacific oysters are displacing native species, which could lead to their local extinction. This would then lead to reduced biodiversity. The Pacific oyster itself is therefore not considered an endangered species.

The Pacific oyster in the Netherlands

The Pacific oyster is considered an exotic species, meaning it does not originally occur in the Netherlands. An exotic species can be transported to a new place either deliberately or accidentally. Accidental, for example, can be because they were lifted along with shipping to a new place where they could settle. This is not the case with the Pacific oyster in the Netherlands.

In fact, this oyster species was deliberately introduced to the Netherlands in 1964 to breed them in the Oosterschelde, Zeeland [1]. This was done because the other, native oyster species in the Netherlands - the flat oyster - was doing badly. Due to overfishing, diseases and cold winters, the number of flat oysters decreased enormously [2].

People thought the Pacific oyster could not reproduce in the Dutch sea because of the low water temperature. This turned out to be the case, and the Pacific oyster spread rapidly. The first outbreak of larvae of the oyster occurred in 1976, the second outbreak in 1982, and then the species was definitely established. At the end of 1976, imports of Pacific oysters were banned, but by then the Pacific oyster had spread [edepot]. The species started spreading in the Wadden Sea in 1983 near Texel [3].

A place in the ecosystem

The species is seen as a pest by some people. An exotic species introduced into a new area can have major consequences. Some species drive out native species, others take an extra or empty place in the ecosystem.

The Pacific oyster has taken the empty spot of the flat oyster. This oyster has a lot of impact on the environment in the Wadden Sea.. Meanwhile, the Pacific oyster has been established in the Netherlands for decades and will not disappear any time soon. What do you think of the Pacific oyster in the Wadden Sea?

As an exotic species, it has no protected status in the Netherlands. This means that small-scale manual harvesting is allowed. You can eat the Pacific oyster: restaurants serve mainly Pacific oysters.

Did you know...

De Japanse oester in Zeeland op het menu staan onder de naam ‘creuse’?

Oysters in the Wadden Sea

In 2002, the first oyster bank in the Wadden Sea was mapped [12]. From then on, the number of oyster beds there increased. In the eastern Wadden Sea, the Pacific oysters mixed with existing mussel beds. But in the western part, the oysters found new places to expand.

Family of oysters

The Pacific Oyster is very similar to the Portuguese oyster (Crassostrea angulata). So much so, that researchers first thought they were the same species. Research from 2010 on their DNA gives evidence that they are indeed two different species. About 2.7 million years ago, they were genetically separated from each other and so for that long they are a different species [6].

The genome of their mitochondrial DNA differs 3%. For your imaging, in humans and chimpanzees this difference is 4% [16]. Because these oysters are so similar, there is a theory that they have a recent ancestor.

The Pacific oyster is native to Asia. The Portuguese oyster was described as originally occurring precisely in the Northeast Atlantic. There is a theory that the Portuguese oyster does originate from Asia and was introduced to Europe at different times in history [7]. It is not yet known where this species originally came from.

Living environment of the Pacific oyster: oyster reef

The Pacific oyster needs a hard bottom to attach to, such as a rock bottom, stones or poles. They may also use shellfish such as other oysters and mussels to attach to.

Oysters are found in littoral areas (always underwater) and sheltered sublittoral areas (is dry with low tide). They can occur at a depth of 4 metres, but in a scan of the Oosterschelde in Zeeland, the shellfish were found at a depth of 42 metres [*].

The Pacific oyster can form a reef with many other oysters. A reef is a shallow area in the sea made on a hard surface. In many places in the world, a reef consists of coral, but in the Netherlands, it is the shellfish that can form a reef. So you have oyster reefs and mussel reefs.

The oyster reef can consist entirely of oysters or a combination of oysters with mussels. Once an oyster has attached itself to a hard surface, this oyster can offer the same hard surface to a new Pacific oyster. This allows oyster reefs to grow continuously. Over time, the old oysters die, but their shells remain.

The environment, such as water flow velocity, affects the formation and maintenance of an oyster reef. If the current velocity is too hard, oyster larvae cannot establish. It can also cause oysters to break off from the reef.

Biobuilder

The environment does not only affect the Pacific oyster: vice versa, the oyster bank also affects the environment of the Wadden Sea. This is why we also call oyster banks biobuilders: a biobuilder is a species that can greatly change its environment. A Pacific oyster does this by:

- Making a hard surface on a sandy area.

- Making the murky water clear so that more light shines through it: the water gets filtered.

Changing the environment so greatly affects other animals and plants living in the Wadden Sea. They provide a different habitat, so this attracts all kinds of living things.

On and between the oyster you will find mussels, but also overgrowth of weeds such as the sea oak. In the lee of the oyster bank and/or the tidal pool that remains after high tide you will find: barnacles, shrimps, crayfish, snails, periwinkles, crabs, anemones, sea squirts. As the top of the oyster bank dries, birds descend on it in search of food, such as spoonbills and turnstones. Fish seek the shelter of the oyster bank and descend on the food found there. A well-known example of this is the mullet.

The influence of the Pacific oyster on other species

Research shows that mussels are more likely to survive on a mixed oyster bed than on a pure mussel bed. The Pacific oysters protect the mussels by making it harder for birds to pick out the mussels between the oysters. On the other hand, mussels on such a mixed bank do have less meat, probably because they have to compete for food with the Pacific oyster [10]. It was also seen in 2016 that the native flat oyster uses shells of Pacific oysters to attach to [2].

Did you know...

The Pacific oyster filters the seawater? This is how the animal gets oxygen and its food.

Diet and foraging

The Pacific oyster filters seawater to get oxygen and eat plants and animals. They therefore depend on the flow and speed of the water, as well as the food in the water [8]. The gills filter the particles they eat. They eat mostly algae (phytoplankton), but also larvae and seeds of other animals such as mussels (zooplankton), bacteria and dead organic matter [8,*]. They also extract lime from the water to grow their shell.

Enemies of the Pacific oyster

The Pacific oyster is itself a prey animal. It is eaten by humans, but also by a number of bird species such as gulls and oystercatchers [4]. Oystercatchers insert their beak into a Pacific oyster that is slightly open, allowing them to spread it open further and eat it.

Gulls drop oysters from the air onto the ground. This is why you often see broken (thrown) oyster shells around the Wadden Sea dykes [5]. In addition, crabs, lobsters, starfish and fish also eat the oyster species [8,*]. There is even a sea slug called the oyster borer that mainly bores open young oysters and eats them [13].

A pearl on the mudflats

Pacific oysters and also mussels can form pearls. This is a reaction of the animal to grains of sand they ingest while filtering the water. Those grains of sand are sharp and the animal protects itself by depositing pearls around the grains. It is quite rare to find a pearl from a Pacific oyster.

Lifecycle of a Pacific oyster

Reproduction

Pacific oysters are hermaphrodites, meaning they can change sex. Larvae of Pacific oysters usually start out male and can change sex during their lifetime.

According to a study in 2020, they can even change sex several times in their lifetime. Not all oysters changed gender. 58% were hermaphrodites, while 42% did not change sex. Of these, 34% were female, and 8% were male. After 6 years of observing every oyster, the distribution had tilted predominantly in favour of females.

At 8-10 months of age, they do not become sexually mature until the water temperature exceeds 12 degrees [9]. Then they can change sex after 3-4 years.

Fertilisation in Pacific oysters

In oysters, fertilisation of the egg takes place in the sea. Female oysters can release between 1,000,000 and 100,000,000 eggs per year [8]. They release the eggs from their bodies. The eggs then float in the water. At the same time, the males also release their sperm into the water. This process happens mainly in the months of July and August, when conditions are right [9]. That means: at least 15-16 degrees Celsius and enough food in the sea. But it can also take place in June and September [15].

Als een eicel een zaadcel vindt, dan wordt het eicel bevrucht en ontwikkelt het zich in 1 dag tot een larve [8]. De bevruchte larven drijven tussen de 15 en 30 dagen rond in zee door middel van de stroming [9]. Dat maakt de larve van een Japanse oester in die levensfase zoöplankton. Zoöplankton zijn dieren in zee die niet of nauwelijks tegen de stroom in kunnen bewegen.

The chances of surviving as a larva are incredibly low. All kinds of fish and other shellfish such as mussels and oysters filter their food out of the water. In the process, they also filter oyster larvae out of the water.

Adult phase

Over 15-30 days, oyster larvae develop a shell. When the shell becomes too heavy to float with, a larva sinks to the bottom to attach itself to a hard surface. They do this with a kind of 'cement' that comes from a gland at the base of their just-developed foot [11]. The oyster is permanently attached to this spot.

Young larvae can detect adult oysters by the substances the adult oysters secrete into the water. Since young oysters have a preference for a place where oysters are already present, they can seek out an oyster reef in this way and thus grow larger [11]. A Pacific oyster can thus reach an age of 20 years [14].

Sources:

- https://www.deltaexpertise.nl/wiki/index.php/OS_Ontwikkeling_populatie_Japanse_oester_VN

- https://www.wur.nl/nl/nieuws/japanse-oester-helpt-bedreigde-nederlandse-platte-oester.htm

- http://www2.alterra.wur.nl/internet/webdocs/pdffiles/AlterraRapporten/AlterraRapport909.pdf

- https://www.nederlandsesoorten.nl/linnaeus_ng/app/views/species/nsr_taxon.php?id=137373

- https://www.ecomare.nl/verdiep/leesvoer/dieren/dieren-van-de-wadden/japanse-oester/

- Ren, J., Liu, X., Jiang, F., Guo, X., & Liu, B. (2010). Unusual conservation of mitochondrial gene order in Crassostrea oysters: evidence for recent speciation in Asia. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 10(1), 394. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-10-394 https://sci-hub.se/10.1186/1471-2148-10-394

- Deborah M. Power, Jonathan W. King, Frederico M. Batista, Ana Grade, Hicham Chairi, et al.. New insights about the introduction of the Portuguese oyster, Crassostrea angulata, into the North East Atlantic from Asia based on a highly polymorphic mitochondrial region. Aquatic Living Resources, 2016, 29 (4), pp.404. ff10.1051/alr/2016035ff. ffhal-01483208f

- Ecologisch profiel van de Japanse oester. https://edepot.wur.nl/18976

- https://www.nederlandsesoorten.nl/linnaeus_ng/app/views/species/nsr_taxon.php?id=137373&cat=152

- https://www.nioz.nl/en/news/japanse-oester-helpt-nederlandse-mossel-een-handje

- https://www.nemokennislink.nl/publicaties/een-ongewenste-vreemdeling/

- https://www.clo.nl/indicatoren/nl1559-arealen-mossel–en-oesterbanken-in-de-waddenzee

- https://www.geintegreerdevisserij.nl/kompas/oesters/voedselweb/

- https://www.geintegreerdevisserij.nl/kompas/oesters/biologie/

- Factsheet oester – Stichting geïntegreerde visserij (2017)

- Varki A, Altheide TK. Comparing the human and chimpanzee genomes: searching for needles in a haystack. Genome Res. 2005 Dec;15(12):1746-58. doi: 10.1101/gr.3737405. Erratum in: Genome Res. 2009 Dec;19(12):2343. PMID: 16339373.

*Jaap Vegter, Stichting Geïntegreerde Visserij en coördinator van het veldstation Waddenloods in Lauwersoog.

On this page

-

External characteristics

-

Distribution and status

-

Family of oysters

-

Living environment

-

Diet and foraging

-

Lifecycle Pacific oyster